The companies are not common carriers anymore; they’re media businesses. Yes, users still contribute posts and comments—though even those, in today’s era of influencers, creators, and AI, are often subsidized and actively shaped by the companies—but the essential content of social media is now the feeds produced by the platforms, not the individual messages posted by users. Go to Instagram and scroll through your feed. It’s obvious that what you’re experiencing is not discrete bits of user-generated content. It’s an elaborate, finely tuned media production manufactured by Instagram for an audience of one: you. The same goes for YouTube, X, TikTok, Facebook, Snapchat, Substack Notes, and, with a few exceptions, all the rest.

The feed is the content, and the social media company is its publisher. Period.

Diffs, by Pierre

Although I’m generally allergic to dependencies as a programmer, I occasionally stumble upon a package that 1) does a thing I really wouldn’t want to implement myself, and 2) is obviously well crafted and likely to be reliable and well maintained. Having great tools in your back pocket, waiting to be leveraged when needed, is a superpower.

So here’s one such tool: @pierre/diffs, available at diffs.com (what a domain name!), is a package for rendering really nice file diffs. And although it comes with a React component, it also has a vanilla JavaScript API as well which is most appreciated.

I used this package in a tool I’ve been building recently, and I was delighted at how simple it was to integrate, and how it respected the existing typography styles in my project.

In a different universe we might have primitives such as this baked into the web platform, but short of that it’s nice to know there’s a well-built tool for this that we can all use. Thanks, Pierre!

For decades, technology has required standardized solutions to complex human problems. In order to scale software, you had to build for the average user, sanding away the edge cases. In many ways, this is why our digital world has come to resemble the sterile, deadening architecture that Alexander spent his career pushing back against.

Assorted thoughts on Sunday's home robot

- Sunday Robotics designed and developed their new robot, Memo, and the platform for training it in stealth over the past two years. No hype events, no prototypes being operated remotely by humans, no promises to change the world. Sunday seems happy to let the result of the work stand for itself: the company’s first tweet was posted just this month! In an age of endless and often fraud-adjacent hype, quiet competence is a refreshing vibe.

- Memo’s form is unique: a friendly, cartoonish-yet-anthropomorphic upper half connected via telescoping rod to a wheeled, rectangular base. Many robotics companies attempt to mimic the human body and in doing so adopt the limitations that come with it. Memo is not bipedal, but in return it has gained the ability to grow and shrink to reach farther than a human could.

- Another side effect of this design is that Memo is never at risk of falling over and hurting someone if it loses power unexpectedly or malfunctions. Sunday calls this feature “passive stability” and, simple enough though it may seem, feels pretty important when considering the practical matter of having a robot moving around your home.

- On the Star Wars/Trek spectrum, Meta falls farther towards the Trek end than many other home robots I’ve seen. That is a very big complement!

- Perhaps a more apt comparison would be Nintendo vs. Sony. Memo could have been plucked right out of a Super Mario game.

- Memo’s physical form is so well crafted that many of the videos of it in action appear to be CGI renders. Sunday assures that they are real, uncut videos, but suspicion comes with the territory these days.

- The best part of the whole thing might just be that you can change Memo’s hat. Visitors to Sunday’s website can even vote for new hat styles (bucket hat has my vote). Because what is the point of owning a robot if you can’t accessorize it?

- Sunday has taken a unique approach to training Memo: human beings wear gloves while performing tasks that restrict their motion to only that of which the robot is capable. Sunday calls these humans “Memory Developers.”

- This training strategy can be contrasted with the approach taken by many of Sunday’s competitors, which is to gather training data via humans operating the robots remotely. But this misses many of the subtleties of how humans actually move. Watching Memo handling delicate stemware makes it clear how the quality of training data translates to real-world performance. There’s an awkwardness in the movement of other home robots which Memo seems to largely avoid.

- The brim of Memo’s hat cleverly houses a downward looking camera for capturing the bot’s field of view. This mirrors the headset mounted camera that memory developers wear in addition to the training gloves.

- Once again we are reminded that the most valuable resource of the AI era, the resource in increasingly short supply, is data generated by the unique experiences of humans. According to Sunday, the going rate for a memory developer is around $60 an hour.

- The idea of “memory development” as a career is straight out of science fiction (looking at you, Blade Runner 2049) and yet, here it is, in 2025, arriving without us ever really noticing. The future can be awfully sneaky.

Now I can think of my sketching and designs in a different way: I am training my intuition. I am not deciding what to do. I am priming myself such that, when a decision needs to be made (when I’m building or somebody asks me for feedback or when I’m putting together the plan for what to build next), I automatically respond the right way in the instant.

This seems like a small twist in framing but actually I find the difference quite freeing: I can see now that I’m no longer meant to be right with my sketches. I’m not supposed to be straight to the point. What I’m doing is scouting the field; I’m loading up my unconscious with everything it needs to make the right choice later, intuitively.

Playing the fiddle

Something I’m noticing about AI, or at least this moment of AI agents and tools for building software, is the extreme amount of fiddling they invite. Fiddling here includes things like trying new models and tools, tweaking prompts, leveraging MCP servers vs. code tools, browsing plugins, installing skills, configuring hooks, setting up subagents, and the list goes on.

The specific knobs you can fiddle vary from tool to tool, but their existence and multitude are hard to avoid. And knobs aren’t even quite the right metaphor here, as turning a knob in the real world tends to have a deterministic effect.

Fiddling with AI can feel like turning knobs on a synthesizer that interprets your choices as suggestions rather than commands.

Take this article by Shrivu Shankar about how they make use of the litany of Claude Code’s features. There’s a lot of helpful stuff in here to be sure, but my biggest takeaway is the sense that the configuration surface is so large, the knobs to turn so numerous, and the interplay between those knobs so mysterious that I could spend an eternity optimizing my setup without ever knowing if the result was meaningfully better or worse.

Then you add on the fact that large language models and the tooling build on top of them is changing rapidly. How is a person who wants to effectively use the best available tools expected to possibly keep up?

Frank Chimero’s recent essay Beyond the Machine reframes this whole dynamic by casting AI as an instrument instead of a tool—something that is not just used but played.

In other words, instruments can surprise you with what they offer, but they are not automatic. In the end, they require a touch. You use a tool, but you play an instrument. It’s a more expansive way of doing, and the doing of it all is important, because that’s where you develop the instincts for excellence. There is no purpose to better machines if they do not also produce better humans.

Instruments also invite fiddling. There are many aspiring musicians who struggle to move beyond endless tweaking, tuning, collecting, or customizing to actually make a tune.

Yet successful musicians fiddle too—maybe even more. Perhaps the trick is knowing when to fiddle and when to play, and recognizing that sometimes those are one and the same.

In other words, instruments can surprise you with what they offer, but they are not automatic. In the end, they require a touch. You use a tool, but you play an instrument. It’s a more expansive way of doing, and the doing of it all is important, because that’s where you develop the instincts for excellence. There is no purpose to better machines if they do not also produce better humans.

Pay attention to Chicago

I’ve felt compelled to write something about what it’s like living in Chicago during the moment we find ourselves in now, but luckily Dan Sinker wrote a piece that I can simply link to and quote here:

What I need you to understand is that nobody is letting them go quietly. The Feds’ every movement is announced by a chorus of whistles, by a parade of cars honking in their wake, neighbors rushing outside to yell to film to witness these kidnappings that are unfolding in front of us. Neighbors running towards trouble.

Like Fred Rogers said, “look for the helpers.”

Don’t miss the resources at the end of Dan’s post about how to contribute your time and/or money. Chicago has always been a bellwether for the country: of dangers to come and hope to be found.

Claude Code as general purpose agent

The more I use Claude Code, the more I find it useful and interesting for tasks beyond the one for which it is named. Simon Willison agrees:

Claude Code is, with hindsight, poorly named. It’s not purely a coding tool: it’s a tool for general computer automation. Anything you can achieve by typing commands into a computer is something that can now be automated by Claude Code. It’s best described as a general agent.

On one hand it’s surprising that this sort of tool is taking the form of a command line interface in the year 2025, but it also makes a lot of sense: CLIs provide programmatic access to your machine and are easy to distribute across platforms.

I often think of the web as the world’s great distribution mechanism (along with the post office), but it lacks the ability to interface with anything outside the browser. This is largely by design and in most cases a helpful feature! But it certainly limits the power of any general purpose agent distributed as a web app.

Native apps have capabilities beyond the browser, but are harder to build and distribute across platforms. That said, I’m excited to see AI companies invest in more general purpose computing agents via native OS integrations. OpenAI’s recent acquisition of Sky is certainly something to keep an eye on.

Whatever you find weird, ugly, uncomfortable, and nasty about a new medium will surely become its signature. CD distortion, the jitteriness of digital video, the crap sound of 8-bit, all of these will be cherished and emulated as soon as they can be avoided.

Art is fused with craft; craft is made of practice; and all of it is stretched across the scaffolding of genre. Empirically, creative work begins with an impulse for WORK, the kind of thing you want to spend your time doing, to which narrative and emotional material is quickly added.

Sharing your information in a smart way can also liberate it. Why is your smartwatch writing your biological data to one silo in one format? Why is your credit card writing your financial data to a second silo in a different format? Why are your YouTube comments, Reddit posts, Facebook updates and tweets all stored in different places? Why is the default expectation that you aren’t supposed to be able to look at any of this stuff? You generate all this data – your actions, your choices, your body, your preferences, your decisions. You should own it. You should be empowered by it.

However, the closed social web has also excluded us from the web. The web we create is no longer meaningfully ours. We’re just rows in somebody else’s database.

Building a private & personal cloud computer

An irony of the personal computing revolution is that, while everyone has a supercomputer in their pocket, a majority of our actual computing has moved to machines in the cloud that we neither own or control.

This surely has some benefits: apps and data are available anywhere and instantly in sync across devices, users are less likely to lose any of their data if their physical device is lost or damaged, and consumers don’t have to worry about the maintenance and upkeep of complicated software.

I’ve written before about the importance of taking ownership of our digital lives. There is indeed a power waiting to be claimed by those who are willing to trade some of those aforementioned benefits for a computing environment that they control.

The web browser is something of a great equalizer here: a universal surface for running and accessing software on any device; the stability of the platform and the ubiquity of its distribution mechanism is unrivaled by the postal service alone. You would expect, then, that the web would be the perfect platform for private, personal software that is owned and controlled by individuals. Unfortunately, that’s often not the case!

Running personal software on the web is a trade off between privacy and ownership. Don’t want anyone to access your private data? You’ll need to implement some sort of authorization scheme and security mechanisms to ensure your data is only accessible to those you trust. Don’t want to manage all of that yourself? Then you’ll need to use a platform owned by someone else that does it for you.

Why is it so hard to scale down on the web? What if there were a better middle ground? Well, dear reader, I’m here to tell you that I’ve found one.

Imagine: a computer you own, connected to a private cloud, accessible anywhere (for free!), running software on your behalf. All of this is easier than it sounds to setup and maintain if you use the right tools. In this piece I want to share how I’ve set this up for myself using a spare Mac mini.

What is a cloud computer good for? Lots of things! Here are just a few examples:

- Run your own software and host your own web apps.

- Host web apps for your family and friends.

- Use Homebridge to do cool smart home stuff.

- Store and stream your own media library.

- Set up automations to organize emails, files, and more.

- Serve as a Time Machine backup destination.

- Run your own local LLMs or MCP servers to plug into other AI tools.

- Have access to a full computing environment on the go from a tablet or smartphone.

- Anything else you might dream of doing with a computer that’s always on and available.

Hardware wise there are lots of options for hosting your own cloud computer, but I happen to think Apple’s latest M4 Mac mini is a superb choice, especially if you’re already familiar with MacOS. It’s shockingly small, whisper silent, plenty powerful, and well priced at a starting point of $599.

This guide will focus on how you can take an off the shelf Mac mini (or really any Mac)and run your own web software that is accessible through a web browser to you and you alone. We’ll make use of just a few free-to-use dependencies.

Configure your Mac

Running a Mac mini as a headless server means we won’t have it connected to a display or keyboard during normal operations. You will, however, need to connect those accessories for these initial steps to set up remote access. I’ve outlined the steps below, and once you have these settings configured you can disconnect the monitor and keyboard permanently.

It’s worth noting that as a side effect of making your Mac remotely accessible we’ll need to change some settings that make your machine less secure to anyone who is able to access it physically. Be sure your device is kept somewhere secure and can’t be accessed by any bad actors.

- Turn on remote management and login

- Before we enable the ability to access our cloud computer from outside our home network, we first want to set up local remote access so that we can connect to the Mac mini from other devices.

- Navigate to System Settings → General → Sharing

- Toggle on File Sharing, Remote Management, Remote Login, and Remote Application Scripting.

- Startup automatically after a power failure

- Navigate to System Settings → Energy

- Toggle on the following settings:

- Prevent automatic sleeping when the display is off

- Wake for network access

- Start up automatically after a power failure

- Automatic login

- This makes sure that if the machine reboots it will automatically bypass the user selection screen and log in as whichever user you choose.

- Navigate to System Settings → Users & Groups

- Select a profile next to “Automatically log in as”

- Never require password to log in

- Navigate to System Settings → Lock Screen

- Select “Never” for “Require password after screen saver begins or display is turned off.”

- Select “Never” for “Start Screen Saver when inactive”

- Enable file sharing

- This allows us to access the filesystem of our Mac mini and any connected drives remotely.

- Navigate to System Settings → General → Sharing

- Toggle on File Sharing

- Disable automatic updates (Optional)

- This step is optional, but I prefer to update my Mac mini server manually during a monthly maintenance routine.

- Navigate to System Settings → General → Software Update

- Click the info icon next to “Automatic updates” to configure your preference.

- Enable Time Machine server (optional)

- If you’d like to use your cloud computer as a Time Machine backup destination for other Macs, you can do so by following these instructions.

Once these settings are configured you should be able to connect to and control your Mac server from another Mac, which is helpful if you choose not to keep a monitor and keyboard connected to your server.

To remote in to your server, open Finder on another Mac and press Command–K to “Connect to Server.” Enter vnc:// followed by the Mac mini’s local name or IP (e.g., vnc://macmini.local or vnc://192.168.1.42) and choose “Share Screen.” If you’ve set automatic login, it’ll drop you straight into the desktop; otherwise, sign in with your user credentials.

This works for connecting to your Mac over your home’s local network, but what about accessing it remotely when you’re away from home? Next we’ll setup a tool that will take care of that for us.

Set up Tailscale

A cloud computer is only useful if you can access it from anywhere, at any time. Ideally we’d like to be able to access software running on our home server over the internet just like any other web app.

This is where Tailscale comes in. Making your Mac accessible over the open internet is a dangerous endeavor that’s easy to get wrong and comes with a host of security issues. Tailscale works around all of that by giving us a virtual private network over which our machines can connect securely, without allowing access from the open internet.

Thanks to Tailscale’s client apps on Mac and iOS, we can connect to our VPN from anywhere and access our cloud computer as if it was any other web server (even though it’s not exposed publicly).

Lucky for us, Tailscale is a breeze to set up and completely free for the purposes described here. There are other tools out there that serve the same purpose, but I’ve been very happy with Tailscale. It’s one of those magic bits of software that just works without any fuss.

Getting set up with Tailscale is simple:

- Go to tailscale.com and create an account.

- Download/install the client application onto your Mac mini server and sign in.

- That’s it!

Well, almost. You’ll also want to do the same on any other devices that you use so that they can connect to the VPN and access your cloud computer. And you’ll want to ensure that the Tailscale app is set to launch on login via its settings panel.

Voila! You now have access to your Mac from anywhere in the world. Tailscale will assign each device on the network with a unique domain name that looks something like machine-name.tail1234.ts.net.

This URL can be used to access your Mac mini remotely via screen sharing, so you can use another device to connect and manage your cloud computer on the go.

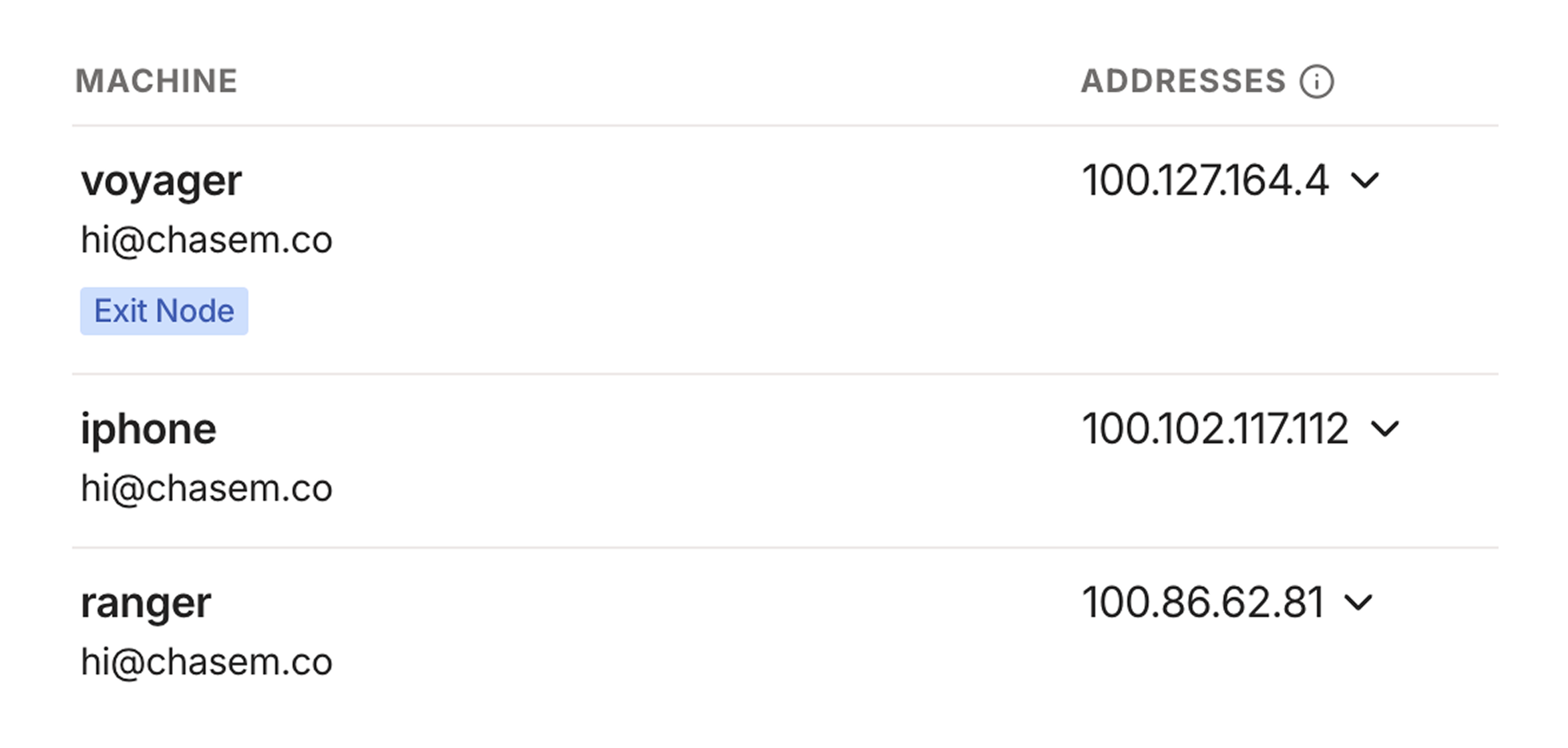

The Tailscale dashboard lists your machines and the addresses associated with each one. It's safe for me to share these because they're only accessible on my private Tailnet, which my devices access via the Tailscale client.

You can now spin up a web server on your Mac and access it on your other devices using the assigned domain name combined with the port. Later I’ll discuss how to set up custom domain names for your services so you don’t need to remember what’s running on which port.

You can also now screen share and remotely control your Mac from anywhere in the world. Simply repeat the steps mentioned above, but replace the local IP or hostname in the vnc:// address with the ones provided by Tailscale.

Manage and access your software

Now that your cloud computer is set up and accessible remotely, it’s time to put it to use!

Any app running on your machine that is exposed on a local port will be accessible over your Tailnet, but we need to make sure that those apps are always running and restart automatically if, say, our machine reboots or the app crashes. For this, we’ll use a process manager called PM2.

Start by installing PM2 globally using npm:

npm install pm2@latest -gNext, we’ll create a PM2 configuration file that specifies the apps we want to run and manage. Execute the following command to generate an ecosystem.config.js file:

pm2 init simpleThat will create a JavaScript config file called ecosystem.config.js in the current working directory. It doesn’t matter too much where you store this file (mine lives in the home directory). The file contents will look something like this:

module.exports = {

apps: [

{

name: "app1",

script: "./app.js"

}

]

}The important bit here is the apps array that contains objects representing the services we want to run and manage. Each app, at the very least, will have a name and a script that should be executed to start the app.

Here’s an example config for one of my apps:

{

name: 'api',

cwd: '/Users/voyager/Repositories/api',

script: 'yarn start',

}This tells PM2 to run yarn start within the directory specified by cwd (current working directory) whenever starting the process.

Once your PM2 config file is ready to go run pm2 start ecosystem.config.js to start up all of the apps defined therein. Swap the start for stop there to stop all of your apps. Check the PM2 docs for all of the available options and commands.

Now that we’ve told PM2 about our apps, we need to make sure it’s configured to start them whenever our Mac reboots. PM2 makes this easy—run the following command:

pm2 startupThis will output a terminal command that you’ll need to copy, paste, and run. Once that’s done, PM2 itself will be set up to run whenever your machine boots.

Finally, we need to tell PM2 which apps should be restored on reboot. Luckily, the config file we created defines all of these, so we’ll just start PM2 with that config and then save the list of current processes:

pm2 start ecosystem.config.js

pm2 saveIf you ever make any changes to your config file, you’ll want to repeat this step to ensure those changes are picked up by the launch daemon.

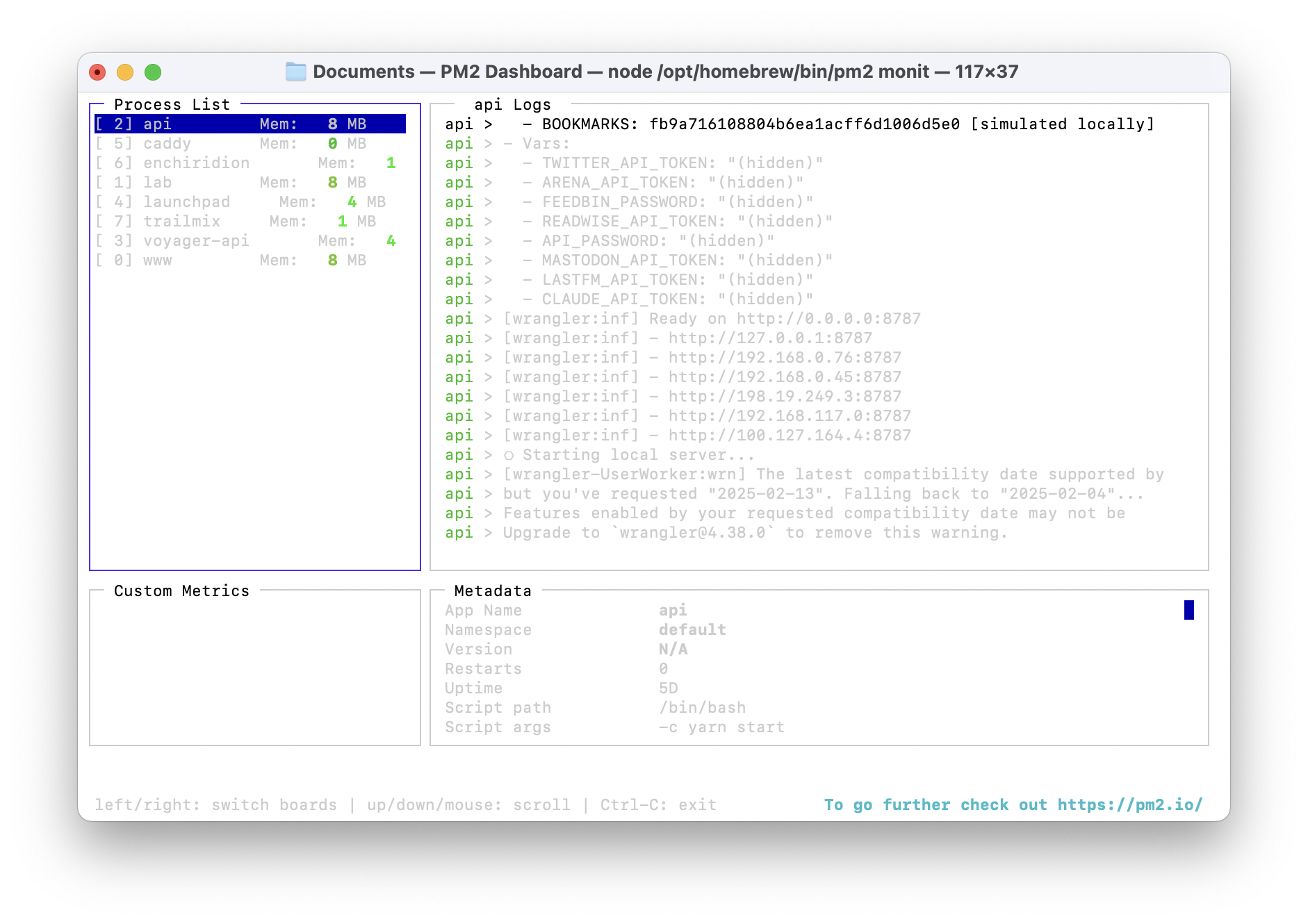

PM2 comes with a great terminal UI for observing the status of your running apps which you can access by running pm2 monit. I like to keep this running in a terminal window on my Mac mini so I can see the status of my apps at a glance.

Custom domains (optional)

The last step in perfecting this setup is to assign custom domains for the apps hosted on our cloud computer. This is nice because we won’t need to memorize or keep track of which app is running on which port number.

There are many way to get this to work, but the solution I found to be the most straightforward uses a combination of Cloudflare as a domain registrar and a reverse proxy tool called Caddy.

You’ll need a domain name registered on Cloudflare that that you’d like to use for your cloud computer. Separate apps/services running on the machine will be assigned to subdomains.

Configure DNS

The first step in this process is to point our domain on Cloudflare to the IP address of our server on Tailscale. Navigate to the Machines tab in your Tailscale dashboard, find your server in the list, and copy the IP address assigned to it by Tailscale. We’ll need that address for the next step.

Next we’ll update the DNS configuration of our domain to have it route to our machine on Tailscale. In the DNS records panel for the domain, create a new A record pointing to the IP address you copied from Tailscale. Use the domain name for the “name” field, and be sure to uncheck the option to proxy through Cloudflare’s servers.

Install and configure Caddy

Caddy will proxy requests to our machine to specific ports, and will take care of setting up an HTTPS certificate for us.

You’ll need to download and install Caddy with the Cloudflare DNS plugin, which can be found here. Select the appropriate OS/platform, search for and select the caddy-dns/cloudflare plugin, right click the Download button, copy the URL to your clipboard, and use it within the following commands.

# Download Caddy with the Cloudflare plugin

# Replace the URL with the one you got from the Caddy downloads page

sudo curl -o /usr/local/bin/caddy "https://caddyserver.com/api/download?os=darwin&arch=arm64&p=github.com%2Fcaddy-dns%2Fcloudflare&idempotency=89062609982188"

# Make Caddy executable

sudo chmod 755 /usr/local/bin/caddy

# Verify that Caddy is installed

caddy --versionOnce Caddy is installed we need to create a Caddyfile to specify which URLs will be reverse proxied to which port running on our machine. Create a file named Caddyfile, stick it anywhere on your filesystem, and update it to look something like this:

(cloudflare) {

tls {

dns cloudflare CLOUDFLARE_API_TOKEN

}

}

lab.chsmc.tools {

reverse_proxy http://localhost:3000

import cloudflare

}

api.chsmc.tools {

reverse_proxy http://localhost:8000

import cloudflare

}You’ll need to replace the CLOUDFLARE_API_TOKEN string with an actual API token acquired from Cloudflare. Navigate to Cloudflare’s API token page in profile settings and generate a token that has zone DNS edit permissions. This step allows Caddy to connect to Cloudflare via its API to ensure SSL certificates are automatically set up for our domain.

In the example above, subdomains of the root domain (for me, chsmc.tools) are reverse proxied to specific ports on localhost. You’ll of course want to update this to match your domain and the ports on which your processes are running.

Finally, we’ll update our PM2 config to include Caddy as one of its managed processes. In the apps array within the PM2 config file we created earlier, add the following:

{

name: "caddy",

cwd: "/Users/chase/Documents",

script: "caddy stop || true && caddy start"

}Make sure the cwd property points to wherever you saved your Caddyfile.

While it requires some initial setup, I’ve been very pleased with this solution both in terms of its usefulness and how little maintenance has been required after getting up and running. I’ve had virtually no down time or cases where my server was inaccessible for any reason, and I only do maintenance about once a month to update the OS, the software running on the device, etc.

It’s also pleasing to know that all of this is running on a machine in my home. There’s something really satisfying about the knowledge that an increasing part of my daily toolkit is code I wrote running locally on a happy, humming machine in my apartment.

The point of all this isn’t to replace the open web: it’s to create a low‑friction space, a laboratory, where we can experiment with and run software without the headache of sign‑up flows, hosting providers, authorization, dependency overload, or vendor lock‑in.

I started by using my cloud computer to run a couple of scripts, but over time I’ve built up such an arsenal of tools that my little machine feels in many ways like more of a companion than the computer I carry in my pocket every day.

For me, perhaps even more than AI coding tools and app builders, this bit of kit has made software feel more malleable and approachable than ever.

Shame is that persistent voice that tells you that you can’t take risks and you need to hide who you are. According to shame, your most natural self is inherently embarrassing or inadequate. But shame whispers in quieter tones, too, telling you that you can’t age and also have a beautiful life, you can’t be poor and also be luminous and unstoppable, you can’t make art if no one knows about it, you can’t experiment and play and laugh and dance if no one approves of how you do it, you can’t feel romance under your skin if you’re not loved unconditionally by one person.

All designers have an origin story, and mine is rooted in a childhood obsession with fictional and futuristic interfaces. I watched science fiction not for the story or characters, but for a glimpse at what a computer could be.

One of my favorites was Star Trek and the LCARS (Library Computer Access/Retrieval System) interface for the ship’s computers. Here is an interface that breaks free from the rectangle! It uses lots of colors and sounds! It’s fantastic.

So I was delighted to see that Jim Robertus has brought LCARS to the web as a free to use, responsive HTML and CSS template. It even comes with sound effects.

I can’t wait to find a reason to build something with this.

Paying attention will increasingly include paying something—even a very micro amount of money—as an attestation that something was viewed. We’ll see novel combinations of taste, limited digital space, and reputation as the read receipts of the post-AI era, when friction doesn’t just signify a barrier to consumption but, rather, the presence of friction indicates that something was consumed.

Regardless of your opinion on traditional media, three things have become abundantly clear:

- Media is no longer the core product of any media company

- Subscriptions as we know them will soon be obsolete

- The rise of AI agents will create net new audiences for media

Cue the rise of agentic capital. A new class of audience using autonomous AI agents trained on their taste to extend their own attention and spending. Suddenly, one person can be worth more than one impression. The average entertainment budget can be more efficiently split across creators, leading to all sorts of opportunities.

Subverting habits means replacing habits. What I’ve learned from my walks is that every day — every step — on the road is a chance for self-renewal, to cast off some small micron of a past, shittier, scared, low-self-worth, less-kind self, and replace it with a more patient, more empathetic, higher value bizarro self. Someone you could have been earlier in life, given a different set of circumstances. Micron by micron, atom by atom, it adds up (one hopes!).

Someone found the real Spotify accounts of famous politicians, journalists, and media/tech figures and scraped their listening data for more than a year. They’ve published some of the data online as the Panama Playlists.

The Panama Papers revealed hidden bank accounts. This reveals hidden tastes.

Scroll in wonder and/or horror!

File this one away as another excellent example of culture surveillance, which I’d argue would make for an excellent entry in an updated addition of the New Liberal Arts.

Antibuildings

We all have our own antilibrary, the books we buy with the best intentions of reading but never quite get around to. For architects, a similar concept might be the sketches and plans that never leave the drawing board: antibuildings?

I’d venture to say there’s likely as much to learn in studying the antibuildings of great architects as there is in studying those works that have been fully realized.

Frank Lloyd Wright left behind a treasure trove of antibuildings (582 that we know of!), and artist David Romero has been creating digital models based on their plans as part of a project called Hooked On The Past. That includes The Illinois: FLW’s ambitious plan for a mile-high skyscraper in downtown Chicago that would have been twice the height of the Burj Khalifa.

Colossal has a great interview with David about his work that features some additional structures I didn’t see on the official website or Flickr page.

Reanimating a ghost

Mary Oliver once said that “attention is the beginning of devotion.” I want to highlight a few examples of this in practice that have recently crossed my desk.

First: the YouTube channel of Baumgartner Restoration, of which I’ve been recently obsessed. The videos feature the proprietor, Julian Baumgartner, narrating the painstaking process of restoring and conserving fine works of art.

There is some peculiar pleasure in seeing a centuries-old painting transformed under steady, gloved hands. It’s not just the ASMR crackle of varnish being carefully removed, or the delicate touch with which he inpaints a lost eyelash on a Madonna’s cheek. It’s the sense that you’re witnessing a dialogue across time: a conversation between the artist, the restorer, and the persistent materiality of the canvas itself.

As a generalist it’s incredible to see the combination of disciplines that go into this sort of work: chemistry, material science, fine arts, woodworking, history, and more. Plus it’s just really relaxing to watch!

One of the foundational principles in art restoration is reversibility: the notion that any intervention made to a work should be removable without harming the original. It’s a kind of humility encoded into the restorer’s practice, a tacit acknowledgment that today’s best solution might be tomorrow’s regrettable overstep. You see this restraint in Julian’s work: the materials he uses are chosen not just for their compatibility with the painting, but for their ability to be taken away if future conservators, armed with better tools or new information, decide to try again.

But what happens when the artwork in need of restoration isn’t made of oil and pigment, but of code and pixels?

A friend recently shared with me the Guggenheim’s ambitious digital restoration of Shu Lea Cheang’s “Brandon,” an early web-based artwork from 1998 (thanks, Celine!).

Brandon isn’t a painting hanging on a wall; it’s a sprawling, interactive digital narrative exploring gender, identity, and the malleability of self in cyberspace. The work, like much of the early web, was built on now-obsolete technologies like Java applets, deprecated HTML, and server-side scripts that no longer run on modern browsers. Restoring this piece isn’t about cleaning and repairing a surface but rather reconstructing an experience, reanimating a ghost in the machine.

Not to mention the piece is made up of 65,000 lines of code and over 4,500 files (!!).

The restoration of Brandon focused on migrating Java applets and outdated HTML to modern technologies. Java applets were replaced with GIFs, JavaScript, and new HTML, while nonfunctional HTML elements were replaced with CSS or resuscitated with JavaScript.

Don’t miss the two part interview with the conservators behind the project. (And please, if I am ever rendered unconscious, do not resuscitate me with JavaScript.)

In the physical world conservation is tactile, direct: a kind of respectful negotiation with entropy. In the digital realm it’s more like detective work, piecing together lost fragments of code, emulating vanished environments, and making decisions about what constitutes authenticity.

There’s an odd poetry in this sort of work. Just as a restorer must decide how much to intervene—when to fill in a crack, when to let the passage of time show—so too must digital conservators choose what to preserve: the look and feel of a Netscape-era interface? The original bugs and quirks? The social context of a work that once existed in the wilds of early internet culture? The restoration of Brandon becomes not just a technical project, but a philosophical one, asking what it means to keep an artwork alive when its very medium is in flux.

In both cases the act of restoration is, at heart, an act of care. A refusal to let things slip quietly into oblivion. It’s love as an active verb, the intentional transfer of energy.

And perhaps, as our lives become more entangled with the digital, we’ll find ourselves needing new ways to honor not just the objects we can touch but the experiences, stories, and communities that flicker across our screens. I personally feel very grateful that there are organizations and individuals taking on this sort of work.

Both of these examples remind us that conservation is less about freezing the past than about paying attention to it, and keeping it in conversation with the present. In that dialogue we might discover new forms of devotion: ways to care, to remember, and to imagine what else might be possible.

Beyond the gamut

It’s not every day that you get to experience a whole new color, and yet: scientists recently viewed an entirely new color by firing lasers to manipulate individual cone cells. No, really!

Most of us don’t have precise eye-lasers at home, but luckily there’s a workaround to approximate the effect. A biological cheat code, if you will.

This blog post over at dynomight.net features an animation you can stare at for a bit and, eventually, you might see the new mystery color. It works pretty reliably for me, and it is kind of wild. My brain doesn’t expect a screen to be able to produce such a saturated color.

You might describe the color as a sort of HDR cyan, but luckily the authors of the paper gave it a much better name: olo.

Olo! To quote the paper, “olo lies beyond the gamut.”

Why do we hallucinate this specific color?

M cones are most sensitive to 535 nm light, while L cones are most sensitive to 560 nm light. But M cones are still stimulated quite a lot by 560 nm light—around 80% of maximum. This means you never (normally) get to experience having just one type of cone firing.

Because M and L cones overlap in the wavelength of light they capture, we don’t get to see the full range of either cone without lasers or mind tricks. Kinda like that myth about not being able to use 100% of our brain power, but in this case: cone power.

• I’ve always seen the browser as a printing press.

• Because of that, I’ve always seen myself as a publisher first and then everything else second.

Most of modern software is industrially produced for mass-market use, so people get used to lazily thinking that is all that is possible. If you can write software, you can build your own kitchen where you can cook your own food. You can host your friends and feed them too. Maybe it will inspire your friends to cook for themselves and invest in their own metaphorical kitchens, too. Hopefully it can be something that grows with you and becomes a part of your every day.

There’s a feeling of thinness that I believe many of us grapple with working digitally. It’s a product of the ethereality inherent to computer work. The more the entirety of the creation process lives in bits, the less solid the things we’re creating feel in our minds.

Thirty years later and I’m still operating on scarcity, still trying to put in the distance between then and now. As if there would never be enough steps. As if that town could reach out and grab me and pull me back at any moment.

Each year you invited me and each year I begged my mother to let me go. Just to observe. I’d be an adoptee there, too, but one swaddled in a vitality we just didn’t have (despite my mom’s concerted and genuine efforts), our tiny family, my quiet grandparents. I would have cut off a leg to sit in the corner of your home, soundless, motionless. To bask in whatever shape your lives took on. To try to understand a fullness I had never known, to wear it like a suit, even if just for a moment. These are the simple dreams of the adopted.

I don’t know if there’s some Platonic or deontic mode of travel, but in my opinion, the most rewarding point of travelling is: to sit with, and spend time with The Other (even if the place / people aren’t all that different). To go off the beaten track a bit, just a bit, to challenge yourself, to find a nook of quietude, and to try to take home some goodness (a feeling, a moment) you might observe off in the wilds of Iwate or Aomori. That little bundle of goodness, filtered through your own cultural ideals — that’s good globalism at work. With an ultimate goal of doing all this without imposing on or overloading the locals. To being an additive part of the economy (financially and culturally), to commingling with regulars without displacing them.

Hopefully I’ve illustrated how pointless it is to try and talk about quality by showing how malleable and variable a term it is.

This slipperiness is also something worth keeping in mind if and when you need to contend with other people bringing up the term. Remember that it is a proxy phrase, often born of an inability or unwillingness to articulate other concerns.

Like “interesting,” “quality” is a neutral word. It is a proxy phrase, and can almost always be replaced by more concrete, constructive, and actionable things that contribute more towards the conversation.

There’s one platform for which none of this is true, and that’s the web platform, because it offers the grain of a medium — book, movie, album — rather than the seduction of a casino. The web platform makes no demands because it offers nothing beyond the opportunity to do good work. Certainly it offers no attention — that, you have to find on your own. Here is your printing press.

The phone, the great teleportation device, the great murderer of boredom. And yet, boredom: the great engine of creativity. I now believe with all my heart that it’s only in the crushing silences of boredom—without all that black-mirror dopamine — that you can access your deepest creative wells. And for so many people these days, they’ve never so much as attempted to dip in a ladle, let alone dive down into those uncomfortable waters made accessible through boredom.

Your job is not to lock the doors and chisel at yourself like a marble statue in the darkness until you feel quantifiably worthy of the world outside. Your job, really, is to find people who love you for reasons you hardly understand, and to love them back, and to try as hard as you can to make it all easier for each other.

These were sad and difficult times in which we all learned that it is often impossible for us as individuals to save someone we love from the sum of their suffering, especially so when you’re ignoring your own needs in the process. But to extrapolate that reality into the idea that we shouldn’t want to tend to our loved ones, to receive them as flawed and imperfect people and care for them anyway, is a grave miscorrection. We all exist to save each other. There is barely anything else worth living for.

But even outside of the material barriers imposed by this kind of standard, I am troubled by its implication: it insists that healing is a mountain to be climbed alone, and that relationships are the reward we get once we’ve reached the summit. When we insist that we could only ever effectively love someone who’s been perfectly “healed” — who will not struggle, accidentally hurt us, trigger us, say the wrong thing, do the wrong thing, or participate in any other uncomfortable display of humanity — we are reinforcing, and perhaps projecting, our own beliefs that we have to be perfect in order to be loved.

Such insistence on forcing love into a meritocracy-shaped mold doesn’t only do a disservice to everyone who dates, it reinforces the idea that any negative, even traumatic, experiences could and should have been avoided, had we done things differently. It’s not quite victim-blaming, but it sure reeks of it.

Here’s something that checks all kinds of boxes for me: Lori Emerson has a gorgeous new book coming soon (April) called Other Networks: A Radical Technology Sourcebook, which you can preorder now from publisher Mexican Summer.

Other Networks is writer and researcher Lori Emerson’s speculative index of communications networks that existed before or outside of the internet: digital as well as analog, IRL as well as imagined, state-sponsored systems of control as well as homebrew communities in the footnotes of hacker culture.

You would be hard pressed to purposely conceive of a book more squarely aimed at my niche interests. And the book itself is a beautiful hardcover tome, rife with archival imagery as well as original artwork. Instant preorder material right here.

By the way, I discovered Mexican Summer and Lori’s book by way of Claire Evans on Bluesky, a site I am spending more time on as of late. Join me, won’t you?

The Model Context Protocol

I really enjoyed this writeup from Matt Webb about extending AIs using Anthropic’s proposed Model Context Protocol. In its own words, MCP is “an open protocol that standardizes how applications provide context to LLMs”.

Back in 2023 I wrote a bit about an early attempt at something similar by OpenAI and was pretty excited about the potential. MCP takes things to another level by making it an open protocol. Anyone can host an MCP server, or create a custom client that works with any language model.

Protocols are cool! And it’s fun to explore them. So I wanted to get a sense of MCP for myself.

I was pleasantly surprised by how easy it was to get started with and see the potential of MCP servers. You don’t even have to build your own as there are lots that have been built and shared by the community. Here’s a great list of reference servers by Anthropic, and there are also over a thousand open source servers available.

If you do want to build your own, I recommend checking out this video from Cloudflare on how to get started using their open source workers-mcp package.

But to quickly get a sense of the potential of MCP, I recommend checking out an existing server first. I decided to start by exploring the Filesystem MCP server which is exactly what it sounds like: a server that gives an LLM access to your filesystem through various tools like read_file, list_directory, search_files, etc. This is great place to jump in and see the potential of MCP.

Adding the server to Claude’s desktop application (one of several clients that currently support the protocol) is as simple as dropping this into the app’s config file:

"filesystem": {

"command": "npx",

"args": [

"-y",

"@modelcontextprotocol/server-filesystem",

"/Users/chase/Notes"

]

}All this is really doing is allowing the LLM to run an npm package which implements an MCP server. Neat!

After restarting the Claude app, I was off to the races. I use Obsidian as my personal knowledge base, and the great thing about it is that it stores notes as plain text on the filesystem. Combined with the filesystem MCP server, I could now ask Claude about my own notes.

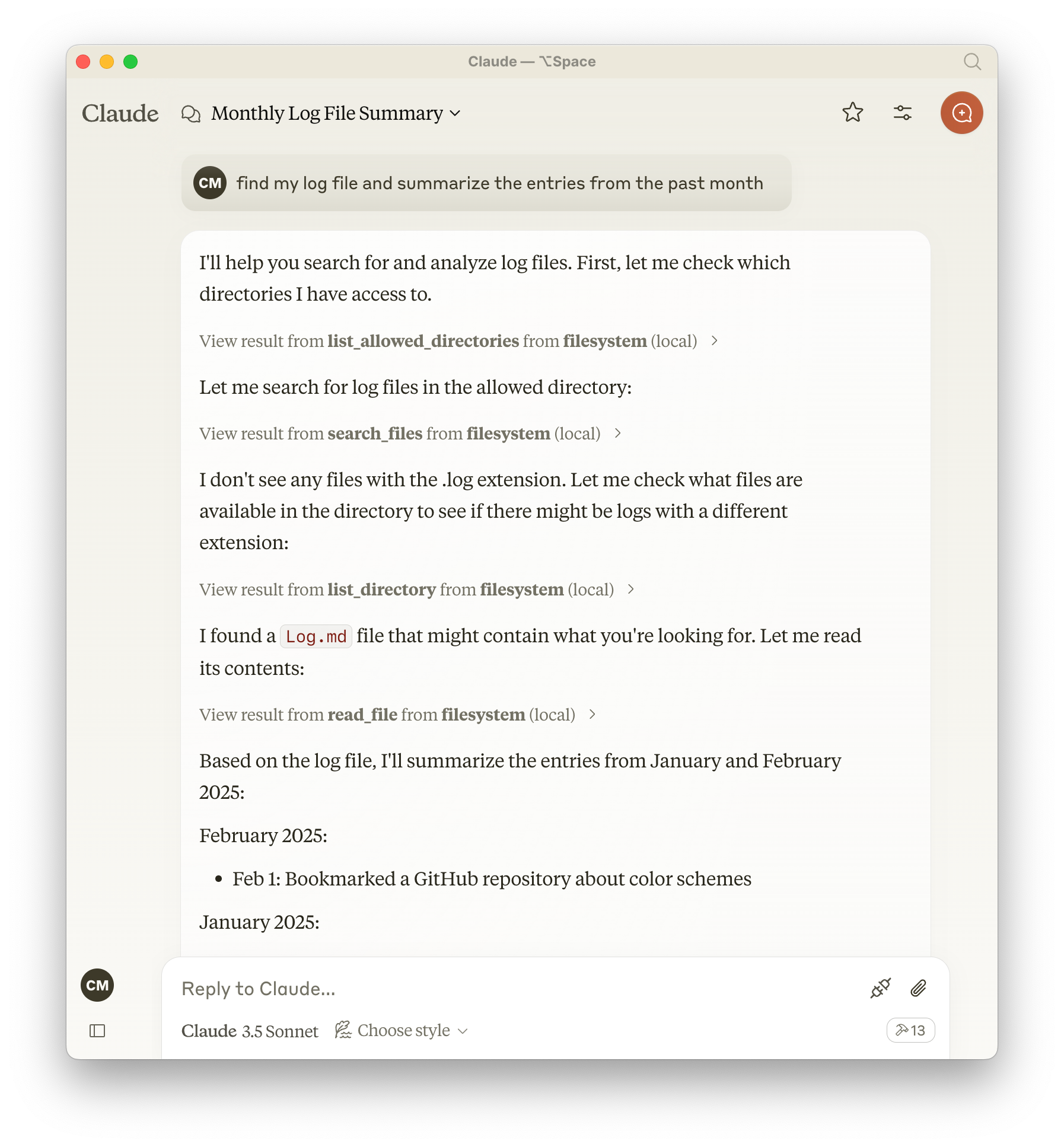

Here’s a screenshot from my very first time using the filesystem MCP server in Claude. I asked it to find my log file (the file I use for running notes throughout a year) and summarize the entries from the past month:

What’s fascinating here is the chain of thought the model goes through, and how it uses the tools exposed via the MCP server to solve problems. It starts by searching for files with a .log extension, doesn’t find anything, and thus broadens its search parameters and tries again. It’s then able to find and recognize my Log.md file, read its contents, and summarize them for me. Neat!

I’m really excited about the potential here to make computers more malleable for the masses. There’s been a lot said about the ability for non-technical folks to create their own apps using LLMs, but the ability for those LLMs to manipulate data and interact with APIs themselves might even reduce the need for a lot of dedicated apps entirely.

](/img/2025-10-06-serve-yourself-garden.png)